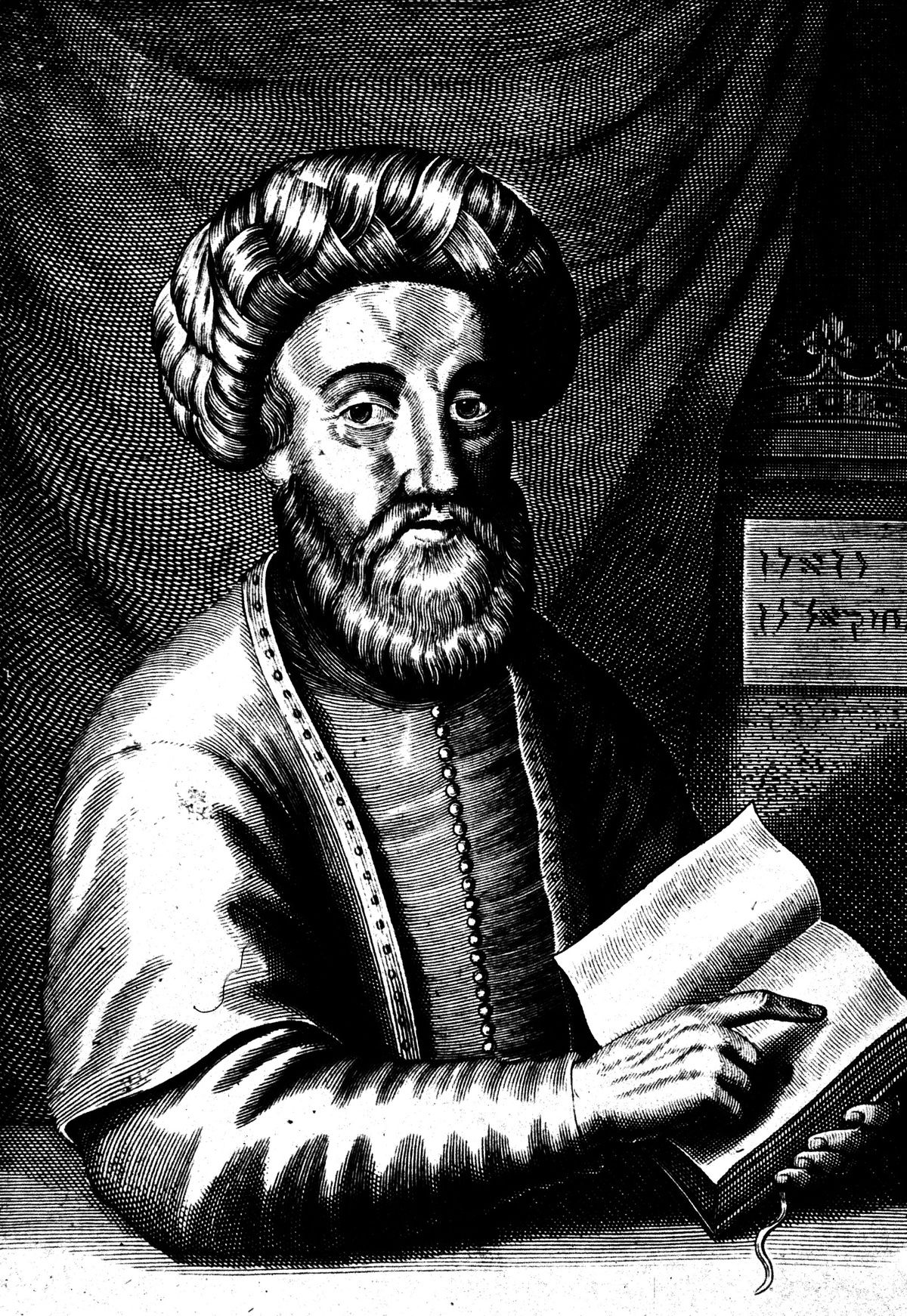

Sabbatai Sevi: The Lost Messiah

In the 17th century news spread that the Jewish messiah had finally arrived. Within a year he had converted to Islam. Who was he, and what had happened?

In late 1665 the Jewish community in Venice was amazed to learn that their long-awaited messiah had come and was living with his wife in Smyrna.

Any other time, they’d have greeted the news with disbelief. After all, there had been plenty of people who’d claimed to be the messiah before. In fact, they’d even seen one themselves. A little over 100 years earlier, they had expelled a dark-skinned dwarf called David Reubeni who had tried to con them with tales of his ‘kingship’. But this one – Sabbatai Sevi – was different.

Strange times

Sabbatai was not an obvious candidate. The son of a prosperous merchant from Smyrna (modern Izmir), he had shown little sign of piety or learning in his youth. At yeshiva he had been an average student at best. The only thing he was interested in was kabbalah, a form of Jewish mysticism; but even in this respect, there was nothing to suggest that he was special – let alone God’s anointed.

Strange times call forth unexpected people, however. The Jewish diaspora was in the grip of spiritual upheaval. Although in some parts of Europe – such as Venice and Amsterdam – Jews lived in relative safety, elsewhere a new wave of persecution was being unleashed. In Poland-Lithuania – once the Paradisus Iudaeorum – more than 100,000 Jews were massacred in the Khmelnytsky Uprising. This led to an upsurge in millenarianism. Jews everywhere put their faith in a ‘great change’ when all would be made good. Some, inspired by a passage in the Zohar, even believed that 1648 was the year the messiah would lead the Jews to salvation.

And so it turned out – at least according to Sabbatai’s hagiographers. One night in early 1648, Sabbatai was walking in solitary meditation just outside Smyrna when he heard a voice cry out:

‘Thou are the saviour of Israel … thou art destined to redeem Israel, to gather it from the four corners of the earth to Jerusalem.’

At first Sabbatai was too terrified to tell anyone but his family and friends what had happened. But from that moment his whole demeanour changed. According to one of his friends, he seemed to be wreathed in an ethereal light. He began speaking the name of God, traditionally forbidden to all but the High Priest of Israel, and even commanded the sun to stop in the sky. This was too strange – too blasphemous – to escape notice of the rabbinical authorities. At some point between 1651 and 1654, they banished him from Smyrna.

Thus began Sabbatai’s long years of wandering. Leaving the city alone he travelled through Asia Minor and into Greece. After a brief stay in Salonika – where he ‘married’ the Torah at a banquet – he made his way to Istanbul. He then snuck back into Smyrna for a while, before travelling through Rhodes to Egypt.

Shortly after his arrival, in early 1662, Sabbatai was introduced to Raphael Joseph, the chelebi (‘lord’) of the Egyptian Jews. Joseph had grown enormously wealthy as an Ottoman official, but he was also deeply pious. He was famous for wearing sackcloth under his clothes and flogging himself until he bled. Sabbatai’s asceticism appealed to him – so much so that he took the strange young man under his protection.

Sabbatai, however, was still restless. After just a few months in Egypt he set off once again for Palestine. He stayed there for about a year, exhibiting all his usual foibles. His natural charm, however, gained him many friends. So much did they come to trust him that, in 1663, they asked him to intercede with Joseph for help with their taxes. He did not need asking twice.

Arriving in Cairo in early 1664, Sabbatai was a changed man. Thanks, perhaps, to the kindness he had found in Palestine, he was calmer, more at ease. He had resolved to stop the absurd behaviour which had caused him such trouble in the past and to live simply, as a rabbi among others.

Wife and prophet

There, Sabbatai’s story might have ended, had it not been for two strange events.

The first was his marriage. This was later so shrouded in legend that it is difficult to establish exactly what happened. Of his bride, Sarah, little can be said with any certainty. Born into a Jewish family in Galicia, in modern Poland, she may have been forced to convert to Christianity as a child. After the Khmelnytsky Uprising, however, her family fled to Amsterdam. There she became a prostitute and started having strange delusions. She became convinced ‘that she would marry the messianic king’. Naturally, everyone laughed at her, but she refused to be shaken and made her way to Livorno. Word eventually reached Sabbatai in Cairo. This reawakened something in him. Convinced that he was destined to marry a ‘wife of whoredom’ in fulfilment of prophesy, he sent for her immediately and married her as soon as she arrived.

Some traditions hold that it was Sarah who encouraged Sabbatai to pursue his messianic pretensions. But it was the second unforeseen happening which proved decisive. At that time there was a man in Palestine named Nathan of Gaza. The son of a noted rabbi, Nathan was a gifted scholar, with a brilliant mind and a profound knowledge of kabbalah. In late February or early March 1665 he had a vision, during which it was revealed to him not only that he was a prophet, but also that a man named Sabbatai Sevi – of whom he had never heard – was the messiah.

Reports of Nathan’s vision reached Egypt soon afterwards. Intrigued, Raphael Joseph sent emissaries to learn more. At first, no one seems to have mentioned Sabbatai’s name in connection with the ‘prophet’, but when Sabbatai learned what had happened he abandoned his work and headed straight for Gaza. It is not clear why he did so. Later accounts suggest that, far from seeking validation, he was hoping to find peace. But when the two met, all that changed. At once, Nathan fell to the ground and hailed Sabbatai as the saviour. Sabbatai was wary. He even laughed. But eventually, he was persuaded.

All Sabbatai’s messianic dreams now burst into the open. In late May 1665 he revealed himself at a prayer service in Jerusalem. With Nathan, his ‘prophet’, at his side his ‘kingship’ was readily accepted by the congregation; his messianic age began. His band of followers swiftly grew. They called him AMIRAH, a Hebrew acronym meaning ‘our Lord and King, His Majesty’. Not everyone was convinced. The rabbinical authorities were scandalised. Denouncing Sabbatai as a heretic, they excommunicated him and drove him from the city.

Accompanied by his acolytes, Sabbatai made for Smyrna, where his journey had begun, so many years before. No longer the timid mystic, he quickly seized control of the Jewish community, pushed out the chief rabbi and began issuing apocalyptic prophesies. Soon, letters proclaiming the ‘good news’ spread across Europe – as did rumours of an imminent Jewish awakening.

Saviour or villain?

In Italy the reaction was swift. Before the end of 1665 a Sabbatean movement was already taking hold. The communities of Verona, Mantua, Turin and Casale accepted the new creed almost en masse. Penitential campaigns sprang up and families made plans to return to the Holy Land. In Venice, however, the response was more cautious. Among the lower classes enthusiasm was marked, but, given how vague the earliest letters were, many rabbis were sceptical – even frightened. And not without reason. Since the foundation of the Ghetto in 1516, the Venetian government had viewed Jews with a suspicion that often bordered on hostile. As soon as the authorities had got wind that something was up, they had summoned the leaders of the Jewish community in for questioning. Prudently, the leaders feigned ignorance – but it was feared that, if Sabbatai’s claims did become known, anti-Jewish riots might follow. Discretion was therefore essential. But it was impossible to quell the curiosity Sabbatai had aroused. Everywhere, people debated whether he was or was not the messiah. By July 1666 a schism seemed inevitable.

By then, however, Sabbatai’s own situation had changed dramatically. Early that year, Sabbatai had left Smyrna for Istanbul amid a flurry of anticipation. Nathan of Gaza had predicted that, if Sabbatai ever returned to the capital, he would depose the sultan and seize the Ottoman Empire for himself. Alarmed, the Grand Vizier, Ahmed Köprülü, immediately had Sabbatai arrested. On 16 September 1666 he was brought before the sultan and given a choice: he could submit to a test of faith, convert to Islam, or be executed on the spot. Sabbatai naturally chose conversion. Now known as Mehmed Effendi, he was rewarded with a sinecure in the palace and a comfortable pension.

The shock of Sabbatai’s apostasy was profound. In Venice, believers were unsure how to react. Some refused to accept he had converted. Others thought it was all a misunderstanding. A third group insisted that only Sabbatai’s ghost had apostatised. Surprisingly, Nathan of Gaza even came to the city to restore their faith. But it was a fool’s errand. The heart had gone out of the movement. The rabbinical authorities forced him to admit he had invented everything and then sent him on his way.

It was not the end of Sabbatai’s story, though. He still lingered on. Given to frequent bouts of depression, he flip-flopped between Islam and Judaism, until eventually even the sultan tired of him. In 1672 he was arrested once again, then exiled to Dulcigno in Albania, where he died four years later. Nor, indeed, was it the end of his adherents. Despite being spurned – and occasionally persecuted – by Jews and Muslims alike, pockets of believers survived. Known in Turkish as the Dönme, they had converted to Islam with Sabbatai, but continued to observe Jewish rites in private. So resilient did they prove, in fact, that in 18th-century Poland a religious leader named Jacob Frank declared himself to be Sabbatai’s successor; even today, a few remain in parts of Istanbul. It may not be much, but for a former messiah, it certainly isn’t bad.

Alexander Lee is a fellow in the Centre for the Study of the Renaissance at the University of Warwick. His latest book, Machiavelli: His Life and Times, is now available in paperback.