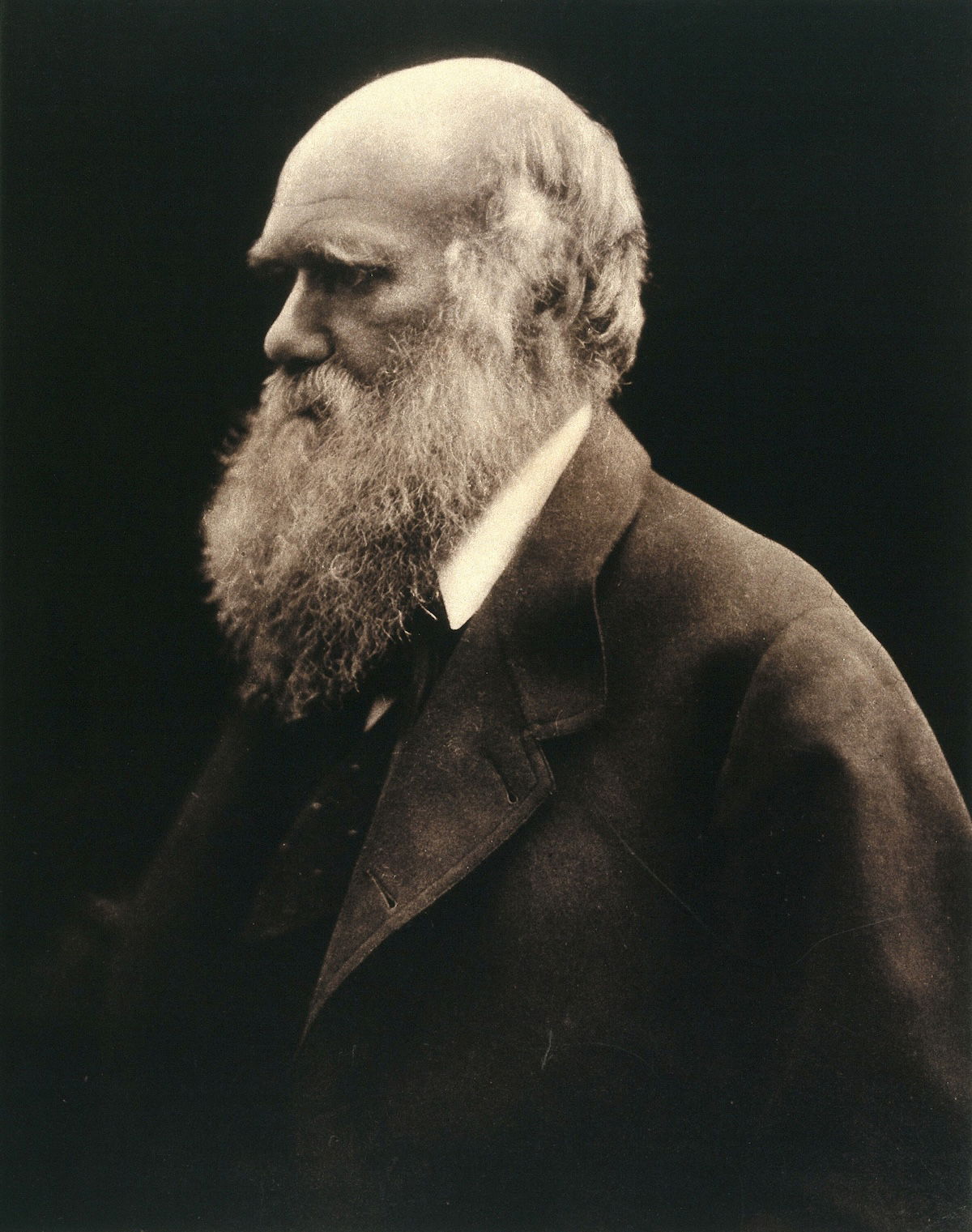

Charles Darwin’s Rocks of Ages

On his early travels across the world it was geology that struck Charles Darwin’s interest, not biology.

Charles Darwin experienced what he recalled as one of the most significant events of his five year voyage aboard HMS Beagle on 20 February 1835: his first earthquake. He was resting from specimen gathering in woods near the southern Chilean town of Valdivia when the quake:

Came on suddenly and lasted two minutes (but appeared much longer) … I can compare it to skating on very thin ice or to the motion of a ship in a little cross ripple … a breeze moved the trees, I felt the earth tremble.

Darwin rushed back into Valdivia where what most struck him was the ‘horror pictured in the faces of all the inhabitants’. He decided that: ‘An earthquake like this at once destroys the oldest associations; the world, the very emblem of all that is solid, moves beneath our feet like a crust over a fluid.’ Further up the coast, at Concepción, Darwin experienced two sharp aftershocks as apparently solid ground beneath his feet transformed into ‘a partially elastic body over a fluid in motion’.

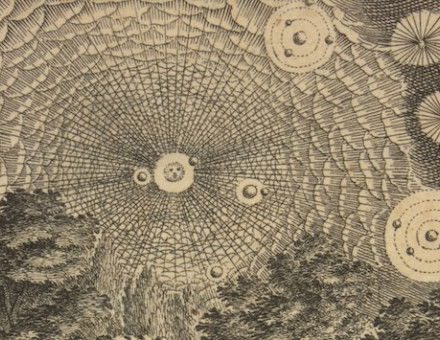

Despite the destruction, Darwin wrote that ‘the earthquake and volcano are parts of one of the greatest phenomena to which this world is subject’. To him, it seemed proof that the theories of geologists such as Charles Lyell – who believed that the Earth’s crust was in perpetual motion – were correct.

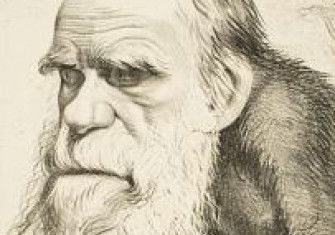

Darwin is remembered primarily as a naturalist, but by his own admission his greater passion during much of the Beagle’s circumnavigation was geology. Within a month of leaving England he was chipping out rock specimens in the Cape Verde islands. However, he made his most significant geological findings during the more than three years the Beagle spent coasting South America. Darwin, who suffered badly from seasickness, was often ashore. Early in the voyage, at Punta Alta in Argentina, he excitedly unearthed the fossilised ‘head of some large animal’ resembling that of a rhinoceros. He also found the fossilised jaw bone of another great creature and nearby some ‘osseous’ (bony) plates, causing him to wonder whether it had possessed an armoured hide like an armadillo’s. These findings not only stimulated Darwin’s curiosity about the geological past but his growing belief that the fossilised creatures he found were related to species still living, an idea key to his later theories about the transmutation of species.

Darwin made several lengthy, sometimes dangerous, journeys into the interior. It seems strange to picture the later reclusive and invalid Darwin galloping across the pampas with an escort of gauchos, who taught him to sleep beneath the stars on his saddle and who drew their knives at the slightest insult, but he relished the freedom. He travelled through bandit-infested wilds, armed with pistols the Beagle’s commander, Robert FitzRoy, had insisted he purchase before they left England.

In March 1835, eager to explore the Andes, Darwin set out with two guides and a mule train from Santiago to cross the mountains to Mendoza and back. Returning across the Uspallata range he saw ‘white, red, purple and green sedimentary rocks and black lavas’, the strata ‘broken up by hills of porphyry of every shade of brown and bright lilacs … [they] literally resembled a coloured geological section’.

Even better, on a 7,000-foot-high green sandstone escarpment Darwin discovered a grove of petrified trees with the patterning of their bark still visible. He later wrote that:

It required little geological practice to interpret the marvellous story ... I saw the spot where a cluster of fine trees had once waved their branches on the shores of the Atlantic, when that ocean (now driven back 700 miles) approached the base of the Andes. I saw that they had sprung from a volcanic soil which had been raised above the level of the sea, and that this dry land, with its upright trees, had subsequently been let down to the depths of the ocean … I now beheld the bed of that sea forming a chain of mountains more than seven thousand feet in altitude.

As with the earthquakes, here were Lyell’s theories brought to life. These petrified trees proved how natural causes operating over long periods of time could create a chain of mountains even as mighty as the Andes. With his geological hammer, Darwin broke off specimens now held in Cambridge’s Sedgwick Museum. Today, only a few fragments of the petrified forest remain in situ, the rest taken as souvenirs or dynamited when a nearby road was rebuilt. But hollows in the sandstone still reveal the trees’ shapes and a plaque commemorates his discovery.

In September 1835, after Darwin’s last overland journey in South America – this time across the volcano-studded Atacama Desert in northern Chile – he and HMS Beagle left South America for the Galapagos, the destination most often associated with the voyage. In these cindery islands, the wildlife – from marine iguanas to giant tortoises – intrigued Darwin, though he did not have the oft-assumed ‘eureka’ moment about evolution there. Not until the Beagle was on the final leg of the voyage did Darwin begin formulating his thoughts on why the mockingbirds found on adjacent Galapagos islands should vary. He puzzled over the two distinct types of ‘wolf like’ fox he had earlier identified on the neighbouring islands of East and West Falkland, wondering whether they shared a common ancestor.

In time, these thoughts would coalesce with conclusions, reached while digging up fossils, exploring Chile and pondering the forces that had created the Andes: that the Earth itself and all life upon it is in constant flux and that our planet is old enough for plants and animals to have evolved through natural selection.

Diana Preston is author of The Evolution of Charles Darwin: The Epic Voyage Of The Beagle That Forever Changed Our View Of Life On Earth (Grove Atlantic, 2022).